1985-2012

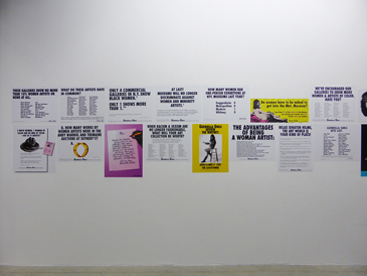

Poster

At the intersection of art and activism, the Guerrilla Girls are an outstanding voice of the latest stage of the feminist art movement. This movement has concerned itself with upsetting fictions like the “artistic genius” and “masterpiece”, which sustain a concept of art that presents itself as independent of its historical and social context. Although forged in the XIX century, this concept continues in force today. The Guerrilla Girls artist collective started its activities in the mid-1980s in opposition to the renewed interest in these fictions that came with the rise of Neo-liberalism. The Members of the group hide their faces behind gorilla masks and adopt the names of iconic dead women artists. Remaining anonymous, they focus on the political dimension of art and denounce the way women are systematically overlooked in contemporary society.

The work of the Guerrilla Girls, who identify themselves as “the conscience of the art world”, marks a turning point in feminist artistic practices for two reasons:

Firstly, their approach to the issues of production and reproduction of sexual difference in art is a discursive turn from previous strategies of feminist art. For the first time Guerrilla Girls offer an overview of the different levels and processes that consolidate sexism in art without ignoring the social and political dimensions of those processes. The Guerrilla Girls’ iconic posters are immediately recognizable because they use the language of statistics to reflect women’s position in the field of art and other areas and they highlight the dramatic failure of democratic societies to keep their promise to achieve equality between the sexes. These posters also form the basis of the collective’s activities, which range from placing them in public spaces, such as on the doors of art galleries in New York, to a variety of actions in museums and other cultural and social institutions.

Secondly, the group’s popularity in the late 1980s marked the end of the first major stage of feminist art, which had been launched on either side of the Atlantic on the back of the feminist movement of the late 1960s. The Guerrilla Girls’ posters, publications and activities acknowledge this heritage; they are constructed from it and they invoke feminist knowledge as the necessary conceptual framework for an acute reading. Above all, the Guerrilla Girls’ work is a reminder that the political aims of the feminist movement of the late 1960s have yet to be achieved and it spurs us on to continue the fight.

Xabier Arakistain