Born in Offenbach-sur-le-Main (DE). Lives and works in Berlin (DE).

2003

2 color ink prints

132 x 216 cm

Year of Purchase: 2013

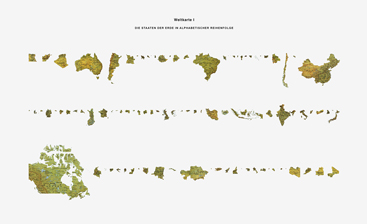

In the early 2000s, Kirsten Pieroth created maps that shook free of the customary codes for representing the world. Her cartographic manipulations first tackled archipelagoes by classifying their islands by size (Griechenland_, 2002) or by name (_Indonesien, 2002). Extracted from the surrounding blue sea and pinned against a white background, each island becomes a specimen in a classification of yet-to-be-proven scientific relevance. With her Weltkarte ([World Map], 2003), Pieroth carries on her project of dismantling and exploding the world map like a puzzle. Hastily cut out, the countries are arranged in alphabetical order on two separate panels, and the division between the two breaks apart the synoptic unity of planisphere. It is therefore impossible to take in the whole world at a glance or trace the mutual dovetailing of neighboring nations.

The implosion of the Weltkarte thus lays bare the arbitrariness of national borders and reinforces the fragmentation of the nations. Carved out by natural boundaries (shores, mountain peaks or rivers), sliced by human treaties, or separated by cultural factors, country contours, winding or rectilinear, alternate between formless and geometric abstraction. Despite its scholarly rectitude, Weltkarte defines an area of knowledge that is far from definitive, since borders are constantly being redrawn by new (dis)agreements or submerged by rising ocean waters. The relationships of scale in turn bring to the fore marked contrasts, such as the insignificance of mini-states versus the immensity of states-continents, without size and power, however, being directly proportional.

Along the lines of maps subverted by conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s, Kirsten Pieroth attacks their very raison d’être: location. Weltkarte is thus a worthy heir to the incomplete map of the United States on which the group Art & Language represented only Iowa and Kentucky, merely enumerating the 48 missing states (Map not to indicate, 1967). Even while taunting the convention and the immaterial character of borders, conceptual artists have also distorted the iconographic and linguistic systems. Ordered by name, the countries in Weltkarte make up an alphabet primer reminiscent of Marcel Broodthaers’ The Conquest of Space. Atlas for the Use of Artists and the Military(1975): a miniature book in which silhouettes of thirty-two countries, represented in identical proportions, are arranged in alphabetical order. Rarely innocent, the linguistic filter immediately betrays the language of the cartographer, often implicit and falsely transparent. Conceived, written, and composed in German, Pieroth’s Weltkarte thus begins with Egypt (“Aegypt”) where the French or the English would have had Afghanistan. This is a way of reminding us that the “order of the world” is never a given, but always a construction.

Hélène Meisel