Born in 1944 Czechoslovakia

Died in 2014

2006

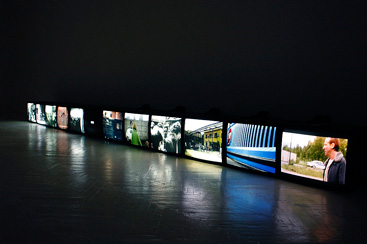

Video installation, 12 monitors, 12 movies clips (b&w and color, sound and not sound)

durée : 36'

Year of Purchase: 2009

Arbeiter Verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzenten (Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades) is an installation composed of a horizontal suite of twelve monitors, each showing a film or a film extract depicting workers exiting the factory from 1895 to 2000. It is an opportunity to gauge the social, technical, esthetic, and political evolution of the fabrication of images, from simple documentary shots to Hollywood staging. Harun Farocki freely juggles diverse registers―commercials, fiction, propaganda, news coverage―organized between a demand for realism and a fictional narrative. Some films bear the signature of such mythical directors as Fritz Lang or Pasolini, while others constitute anonymous accounts. At the head of, and at the end of, the list are La sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon ―the emblematic “first film” in the history of cinema, shot in 1895, and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000). Within the intervening time between the production of these films, about a clip per decade illustrate the polymorphous character of this iconic representation of industrial modernity: in color or black and white, silent or accompanied by dialogues or commentary. We recognize real workers, hurriedly clocking out before their “liberation,” next to more archetypal ones, played by actors, such as Charlie Chaplin or Marilyn Monroe. The first task of adaptation: identifying the real and the fake, even if one knows that the gateway to the Lumière factory might have been itself a stage set, in the manner of “docufiction.”

This thematic array provides a pretext for tackling the theme of labor in a way that is both literal and metaphorical. It is literal insofar as the factory exit marks the concrete, physical threshold between work and leisure, between consensual servitude and free time, between the rigid social function of the worker and the private sphere. It is a boundary which represents a strategic point of ephemeral assembly, and hence the privileged theater of protests, strikes, sit-ins, and manifestations. The fence, omnipresent in all film extracts, constitutes a double object of confinement and deliverance. It appears, for example, as a symptom of imprisonment in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis which shows damned workers, or it is glorified in a 1980s’ corporate video shot over a heroic soundtrack. But the perception of labor takes place also at a metaphorical level. Through this visually cacophonic dialectic, Farocki illustrates the popular saying that “life begins when work ends” by connecting it directly to the rise of the cinema which was greatly responsible for the society of entertainment and of the spectacle. This mise-en-abîme in turn brings to mind the fundamentally political character of cinema which was an industry before it was an art―a fact which is strongly imprinted on the famous scene from the Lumière Brothers’ film. Farocki’s installation reflects in images precisely on these two branches of the seventh art―fiction and documentary―which have been intertwined from the very beginning. The audiovisual borrowings are enriched as a result, and come to tackle other themes, such as social struggle, colonialism, or corporate communication, in their current relevance rather than in nostalgia. This chronological frieze of an endlessly repeated scene sketches the figure of eternal rebeginning, as if the very image of voluntary servitude of the working class hadn’t evolved and remained a fixed point in the course of the evolution of images.

Guillaume Désanges