Born in 1963 in Santiago (CL)

Lives and works in Geneva (CH)

2000

Video, colour, sound

Durée : 11'50"

Year of Purchase: 2004

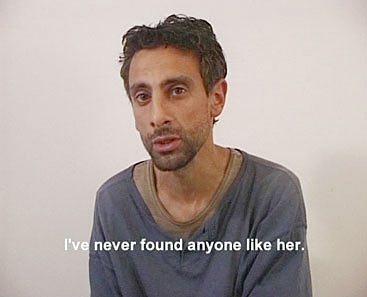

In the title of Ingrid Wildi’s video Si c‘est elle (If it is her), the ‘if’ is not as innocent as it looks; it opens up the work to a sum of possibles. Three men seen face on in close up against a white ground bear witness one after the other. They tell of a woman they have loved in a distant or not so distant past, we don’t know. The words cross over, mixed together by the editing. Although we can’t be too sure, our initial reaction is to believe that they are describing one and the same person; the portrait becomes romantic. Gradually this foolish and wise virgin, capable of dumping you right in the middle of a film show, comes to life for us through the voice of her loves. She was unique, a bit of a healer, wearing skirt and high heels, she was singing, not singing … These concordant accounts then begin to diverge; as it all comes out, the single heroine of a complex, captivating novel (this is what we see in the eyes of those telling the story) vanishes, becoming multiple, and we understand that each eyewitness is chasing after their own character, depicting her with a charge of emotion that, reading between the lines, tells us as much about themselves as about this woman they are describing. The meeting of these stories builds up a baroque narrative framework that resembles an inquiry for the viewer. Is she a lover? A friend? At last we feel we know who it is without actually being told: three grownup children are talking about their mother. As often in her work, in Si c’est elle Ingrid Wildi combines the universal and the personal, calling indirectly and with sensitivity upon her own story, that of a Chilean expat who came to Switzerland at the age of eighteen and was forced to leave behind her roots, her language and her mother. At the same time as it resonates in each of the viewers, the testimony of the three men seems to hark back to the artist’s own obsessions. Si c’est elle is the building up of the picture of one’s mother through the prism of memory. It is a quest for origins formulated through language. Ingrid Wildi contrives with this refined device to construct a delicate work in which this talking at cross-purposes flips the life experience over into a form of narrative. Reconstruction by evocation has their testimony constantly drifting between the real and the imaginary. The woman of the story becomes a character. Memory writes up a whole world within an interstice. Its approximations, its convolutions, its ellipses (added to those of the editing), give the video-essay, for that is how the artist describes her work, the paradoxical strangeness of the familiar world. Memory and the unconscious become the constituent elements of a kind of ‘real-life abstraction’.

Speech is the tool enabling a possible ‘fictionalization’ of reality. The artist has an unusual relationship with it. ‘My own language is not mine’, she says. To speak a foreign language, make it one’s everyday language, is to move at each moment on a different level of reality. ‘The exile’, writes Jankélévitch, ‘has a ghostly life that is lived on the fringe of the first one […] a dreamlike, unreal existence.’ The persistent impression of vacillation that we discern with respect to the work may be seen as the sign of this same feeling of strangeness that haunts the artist’s life. Through language, the spoken word, a world is (de)constructed. Si c’est elle appears as the expression of a rare, melancholy universe built on the quest for each person’s ‘mother tongue’.

Guillaume Mansart