Born in 1968 in Zurich (CH)

Lives and works in Zurich (CH)

2001

Drawing video

Version moniteur

Durée : 2'

Year of Purchase: 2002

If there is one ordinary moment in our lives that seems, with good reason, to resist the narcissistic call of the media sirens, it has to be when our awareness seems to take leave of us as it plunges into some dream worlds. The subject, despite the obvious lack of concessions to the showbiz society,1 has nevertheless fuelled a few episodes of a new TV genre that tries in vain to convey the strange power of ordinary reality. In this undertaking, filming someone while they are sleeping has only one interest: in contributing to attempts at capturing reality. It is the detail that is unimportant in itself and significant for the setting, the one that justifies all the rest, the superfluous detail. Sleep as seen by the media eye plays the role of the barometer described by Flaubert, serving no obvious narrative purpose, in A Simple Heart, the very purpose Roland Barthes describes as a pure effect of reality. ‘Flaubert’s barometer ultimately says nothing but this: I am reality.’2

When Zilla Leutenegger sets about representing sleep, she above all avoids turning it into an indicial argument. Rather than considering this moment of abandon in terms of means or residue,3 she chooses to write it in as an independent element. The media exhibition and reality then make way for poetic imagination and privacy. From the seemingly obvious to the subtle.

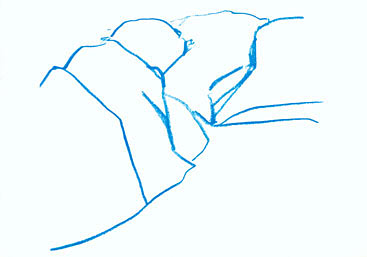

Odds for tonight is a work that combines drawing and movement. Against the black ground of the projected image, a few lines looking like chalk lines4 depict a form that we at first take to be abstract and motionless. It turns out to be a drawing of the artist caught under her bedclothes and which is finally turned over after a few moments to reveal her face and laid down hand. Her light breathing, gradually becoming more present, gently lifts the weight of the bedclothes. This lends the video-drawing a quiet, soothing rhythm as the sign of rest. The movement is so slow that time is suspended, the picture of sleep is stretched to infinity (the work is a loop). ‘I like to consider my drawings as failed because I like their weakness, their perpetual searching, and their unconventional way of succeeding, through what they ought to be’, says Zilla Leutenegger.5 Odds for tonight toys with this incompleteness, this absence which permits intrusion. And a dreamlike projection is soon superimposed over this slight image of the sleeping body.

In the vocabulary of psychoanalysis the term ‘dream screen’ describes the imaginary plane on the surface of which the dream is said to take place. All dreams are projected onto a white screen, generally unknown to the dreamer, symbolizing the mother’s breast […]; the screen satisfies the desire to sleep.6 So it is a kind of catalyst, and the dream a projection. A concept such as this can only resonate in the work of Leutenegger. And while Odds for Tonight opposes the serene shadow of crushing night to the white of the mother’s breast, the work is nonetheless a space open to the projection of the imagination, a ‘dream screen’ that is paradoxically both private and collective. For the video-drawing, contradicting the eye through its intrinsic distance (the body’s absence to itself), inevitably calls upon fresh ones. Rather than one more narcissistic view of oneself, Zilla Leutenegger’s work is a generous poetics that draws a cosmos within a microcosm.

Guillaume Mansart

1 As the well-known Andy Warhol film Sleep can show us.

2 Roland Barthes, ‘L’effet de réel’, in Communications, 11, 1968 ; reprinted in Littérature et réalité, Seuil, Paris, 1982.

3 ‘Realists, writes Gaston Bachelard, refer everything back to daytime experience while ignoring nighttime experience. For them, the night life is always a residue, a sequel to the waking life’, in La terre et les rêveries du repos, Libraire José Corti, Paris, 1948.

4 The four versions of Odds for tonight intended for showing use the same colours, dark background and white line, whereas the four versions intended for broadcasting on a monitor are negatives,

i.e. the drawing is in blue on what is now a white background.

5 ‘Zilla Leutenegger, You’re Innocent When You Dream’, interview with Michele Robecchi, in Flash Art, Milan, May–June 2004.

6 A phrase coined by B.D. Lewin, quoted in J. Laplanche and J.-B. Pontalis, Vocabulaire de la psychanalyse, Quadrige, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1st edition 1967.